Once, the landscape functioned like a commons in practice, even if not in law. Rivers were workplaces, playgrounds, and proving grounds all at once. Towns leaked into the hills and the hills leaked back into town. Rodeos weren’t “events” so much as eruptions—what happened when people, animals, land, and boredom intersected. Risk was tolerated because life itself was risky. Culture wasn’t scheduled; it happened when enough people showed up and no one stopped them.

In the old Idaho, the land was a partner in a difficult, often dangerous dance. Today, it has been reimagined as a therapeutic backdrop.

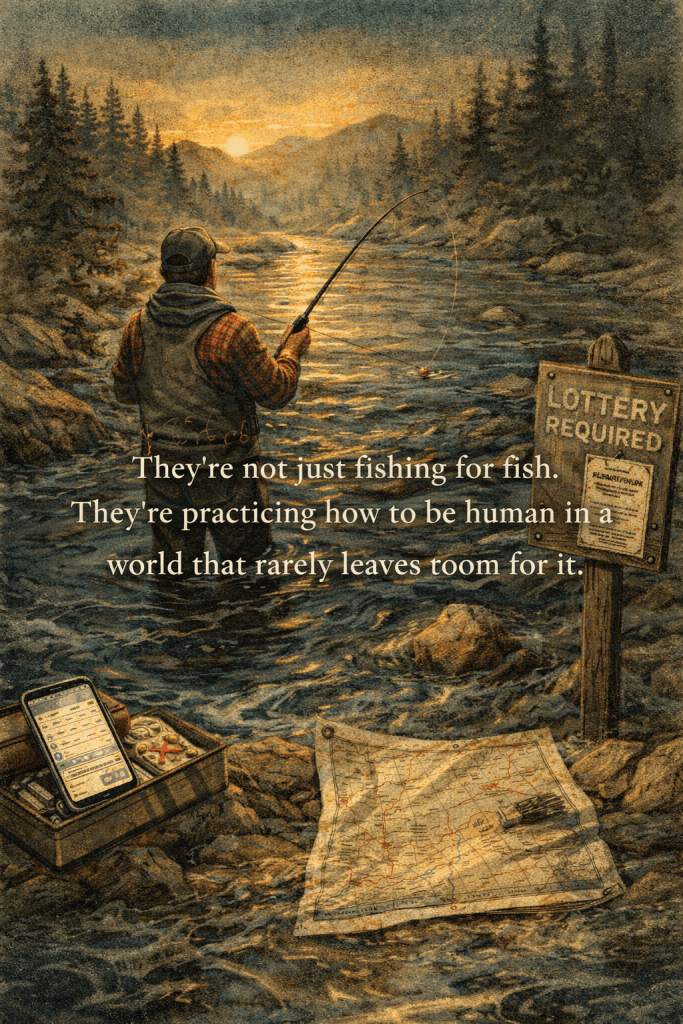

Now the outdoors are curated the way museums curate artifacts. Nothing is accidental. Trails are engineered for flow and liability. Access points are signed, mapped, insured, and optimized. Rivers are managed like delicate exhibits—float times, boat launches, seasonal closures, species restrictions. Even solitude has rules. When a river is managed for “flow and liability,” it ceases to be a force of nature and becomes a utility. We no longer ask what the land requires of us; we ask what the land can provide for our “wellness” or our “brand.”

The land still looks wild, but the system around it is precise, bureaucratic, and heavily narrated.

This isn’t just Idaho, but Idaho does it with a particular polish. The state sells a frontier image while enforcing post-frontier control. The branding says freedom; the regulation says predictability. Nature becomes lifestyle infrastructure—something you use correctly rather than something you negotiate with. The outdoors turn into a showroom: clean, safe, photogenic, and consumable in weekend-sized portions. The transition from a local resource to a global destination means the land must be “dumbed down” to the lowest common denominator of safety.

We used to walk game trails or ridgelines where the path was a suggestion. Now, trails are built with grade reversals and armored switchbacks to prevent erosion and lawsuits. We follow the yellow brick road of the Forest Service, and in doing so, we stop looking at the horizon and start looking at our feet.

The professionalization of play follows naturally. You can no longer just “go” to the mountains; you must “gear up.” The industry demands the specific carbon-fiber tool for the specific, regulated activity, and people buy it. Participation now requires a prerequisite of high-end equipment, which acts as a secondary gatekeeper to the commons.

The rodeo example is telling. Rodeos didn’t vanish because people stopped liking them. They vanished from daily life because unscheduled risk is no longer socially acceptable. Liability, insurance, zoning, noise ordinances, and audience management didn’t kill the rodeo; they domesticated it. Culture didn’t die—it was contained. What used to spill into streets and backyards now lives inside fenced time blocks with wristbands and sponsors.

In the un-curated West, culture was a byproduct of survival and proximity. Now, culture is something that is delivered to an audience. When an activity becomes an “event,” it requires a permit; a permit requires insurance; insurance requires a fence. The fence doesn’t just keep people out; it keeps the experience from leaking into the community. We have traded the jagged edges of a living culture for the smooth, sanded surfaces of a hospitality industry.

And this is where people changing really matters.

Once discovery became mass access, scarcity entered the picture. A river known to ten families behaves very differently when it’s known to ten thousand strangers. The system responds not with trust, but with control. Rules appear not because people are bad, but because volume destroys informality. When everyone arrives, nobody is allowed to behave freely.

The sturgeon example cuts to the bone. There was a time when catching a giant fish was a private contract between angler and river. Now it’s a managed interaction. White sturgeon didn’t become protected because humans suddenly grew moral. They became protected because abundance met extraction at industrial scale. We protect the fish not because we love it in its own right, but because we need the idea of the fish to remain viable for the next user. What was once awe became data. Length limits, catch-and-release rules, monitoring—these are the price of mass participation. The fish survive, but the myth dies a little.

This creates a psychological distance. When every interaction is mediated by a signpost or a digital permit, awe is replaced by a checklist.

The hassle of the outdoors—getting lost, breaking down, running out of water—was what created the myth. Now, with satellite GPS and groomed corridors, the wild is just another room in the house, albeit one with better views. In the old way, a secret fishing hole was a piece of oral history passed down. In the new way, it is a pin on a crowded map app. When secrecy dies, intimacy dies with it. You cannot be intimate with something that ten thousand other people are also liking simultaneously.

So, the tension isn’t really between freedom and regulation. It’s between intimacy and scale.

Idaho’s outdoors are still there, but they no longer tolerate improvisation. You can enter, but only in the correct way. You can participate, but not alter. You can experience, but not leave a mark. The land becomes something you visit, not something that lives alongside you.

That’s why it feels gated even when it’s technically open. The gates aren’t fences; they’re schedules, permits, norms, and expectations. Time and money become the true access keys. If you work constantly, the outdoors shrink into postcards and hashtags. If you have flexibility, they expand—carefully, legally, within bounds.

Perhaps the most biting part of this shift is the scheduling of freedom itself. In the post-frontier West, spontaneity is the enemy of the system. If you want to float the Middle Fork, you enter a lottery years in advance. If you want to camp, you book a site six months out at midnight. This rewards the technocrat and the wealthy—those who can plan their lives in rigid blocks. It punishes the local and the worker, those whose lives are still dictated by weather, harvest, or immediate need.

The outdoors haven’t just been gated; they’ve been synchronized. We have conquered the wild not with axes, but with calendars. The blood has been drained, replaced by the steady, predictable pulse of a spreadsheet.

What was once a backyard has become a product. Still beautiful. Still powerful. But no longer messy, dangerous, or culturally alive in the same way. The wild didn’t disappear—it was stabilized. And stability, while safe, has a way of draining the blood from things that used to breathe on their own.

So why fish at all?

Because fishing still operates on an older logic.

There is no single “right way” to fish. There are parameters—water, weather, season, species—but within those boundaries, fishing bends to the person holding the rod. Skill matters. Attention matters. Preference matters. Trout, especially, don’t tolerate shortcuts. You can’t overpower them. You have to meet them where they are, on their terms. You wouldn’t throw an eight-inch swimbait into a narrow creek any more than you’d shout at the river and expect it to listen.

That’s the point.

Fishing resists optimization. It refuses guarantees. The idea that success comes down to luck never quite holds up, because over time patterns emerge. Adjust the depth. Change the presentation. Read the water better. What looks like luck to an outsider is often repetition paired with attention. Knowledge doesn’t remove uncertainty—it just makes uncertainty navigable.

The best time to fish is when you can. Not when the calendar allows it. Not when the app says conditions are perfect. When you can. I’ve fished in winter and caught nothing while someone upstream did fine. The mistake wasn’t the season. It was the approach. Fishing exposes error without apology. The water doesn’t care how prepared you feel.

Where you fish matters, but not in a way that can be fully mapped. Structure, current, energy conservation—eddies behind rocks where trout can hold with minimal effort. These aren’t secrets so much as invitations to pay attention. They reward people who look instead of scroll.

And how do you fish? With a hook. Everything else is secondary. You can own expensive gear and still fail if you miss the fundamentals. Fishing has a way of stripping things back to what actually matters.

Fishing also reveals things you didn’t set out to find.

Sometimes it’s practical. A different line through a run. A change in retrieve. A pause that turns nothing into something. These discoveries don’t come from instruction; they come from staying long enough to notice what isn’t working and refusing to leave too early.

Other times it’s personal.

When there’s nothing left to react to, your thoughts stop performing. Memory surfaces. Frustration does too. So does clarity, occasionally. Fishing doesn’t resolve any of it. It just removes the usual distractions and lets whatever’s there rise to the surface. You learn what you do when nothing is happening. Whether you adjust, get impatient, or stay with it says as much about you as it does about the water.

That’s part of the older contract. The river doesn’t just teach you how to fish it—it teaches you how you respond to uncertainty, repetition, and silence.

But the deeper answer is this: fishing gives you time back.

Sitting on the riverbank, casting into open water, letting the lure drift—there’s space there. Space for the rod tip to twitch. Space for the current to pull. Space for the mind to wander somewhere it usually isn’t allowed to go. Your hands stay busy while your thoughts go unguarded. No screens. No notifications. No one asking anything of you. Just repetition, water, and whatever you’ve been avoiding.

Fishing doesn’t demand urgency. It demands presence.

That’s why it still works in a world that has been stabilized, scheduled, and fenced. Fishing hasn’t escaped management—but the act itself still carries the older contract. You negotiate directly with the river. You learn through failure. You accept that you never fully know. And in that acceptance, you become a student again, not a consumer.

Maybe you catch a fish. Maybe you don’t. Either way, something happens that doesn’t fit neatly into a spreadsheet.

And in a landscape that has been synchronized, optimized, and drained of blood, that might be reason enough to keep casting.

The way people fish now isn’t an accident. It mirrors the culture they live in the rest of the week.

We inhabit a world optimized for speed, certainty, and explanation. Most things arrive pre-packaged, pre-approved, and pre-explained. Mistakes are expensive. Idleness looks suspicious. Silence feels unproductive. The expectation is that if something matters, it should be efficient, documented, and repeatable.

Fishing offers the opposite—and that’s why it attracts the kind of angler it does.

Many people come to the water already conditioned to measure success: fish caught, distance covered, conditions logged, photos taken. Apps track effort. Gear promises advantage. Information piles up until the experience starts to feel like a task. This isn’t wrong—it’s cultural gravity. People bring the systems they live under with them into the outdoors.

But the anglers who stay—the ones who keep coming back even when the fishing is slow—are often responding to something deeper. They recognize, sometimes without naming it, that fishing is one of the last places where uncertainty isn’t a failure. Where not knowing isn’t a flaw. Where attention counts more than optimization, and presence matters more than outcome.

That’s why so many anglers talk the way they do. Why they value “figuring it out” over being told. Why they defend methods that don’t scale, spots that aren’t marked, and techniques that can’t be explained in a sentence. They aren’t resisting progress—they’re protecting a way of relating to the world that hasn’t been fully absorbed by systems yet.

In a culture that demands performance, fishing allows patience.

In a culture that schedules everything, fishing allows drift.

In a culture that sells certainty, fishing insists on “you never know.”

That isn’t nostalgia. It’s adaptation.

Fishing survives not because it avoids modern life, but because it offers a counterweight to it. A place where effort doesn’t guarantee reward, where failure teaches more than success, and where the only real requirement is that you show up and pay attention.

That’s why, even now, even managed and mapped and regulated, people still stand in cold water and cast into uncertainty.

They’re not just fishing for fish.

They’re practicing how to be human in a world that rarely leaves room for it.

Leave a comment