Today there is a substantial amount of species in the vertebrate classes; an estimated 27,000 living species. Not included in this total is the fish class, “Pisces,” which has a growing number of around 25,000. Sharks and lampreys would, at first glance, be thought to be in separate classes, as sharks have jaws and lampreys do not. This would be thought to be a significant step in vertebrate evolution and would suggest placing the Agnatha, or jawless fish, in a class of its own. However, Agnatha is too deeply rooted in the “Pisces” class for it to be abandoned outright. Text suggests that Pisces is not monophyletic, or derived from a single ancestor, but instead from a group of ancestors. Although this remains highly debated, these organisms share several defining features that strongly suggest derivation from a common ancestral lineage.

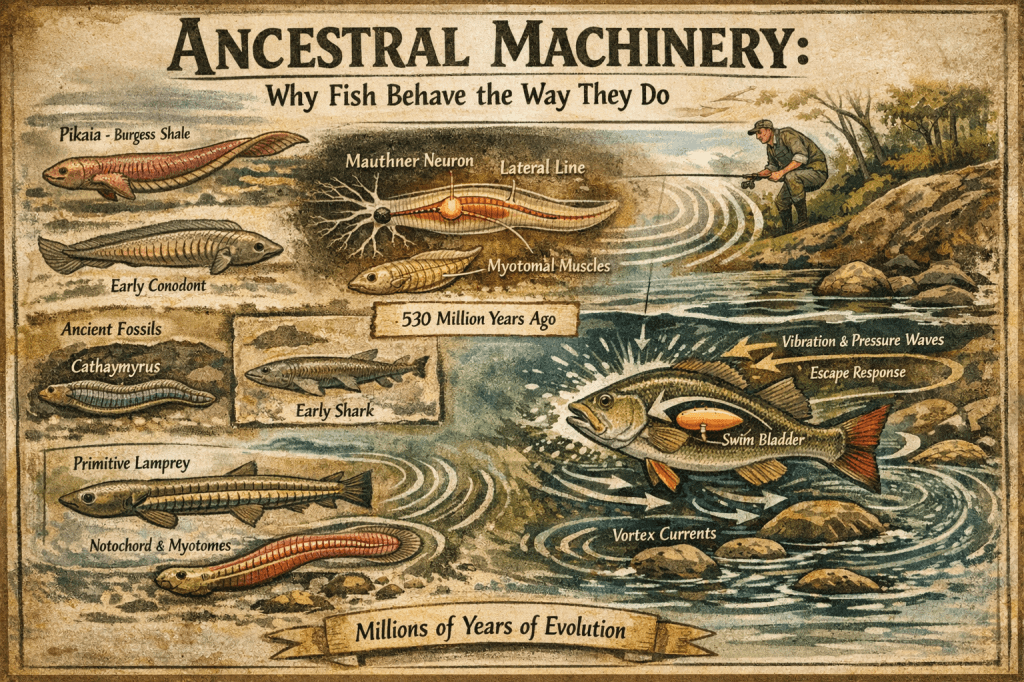

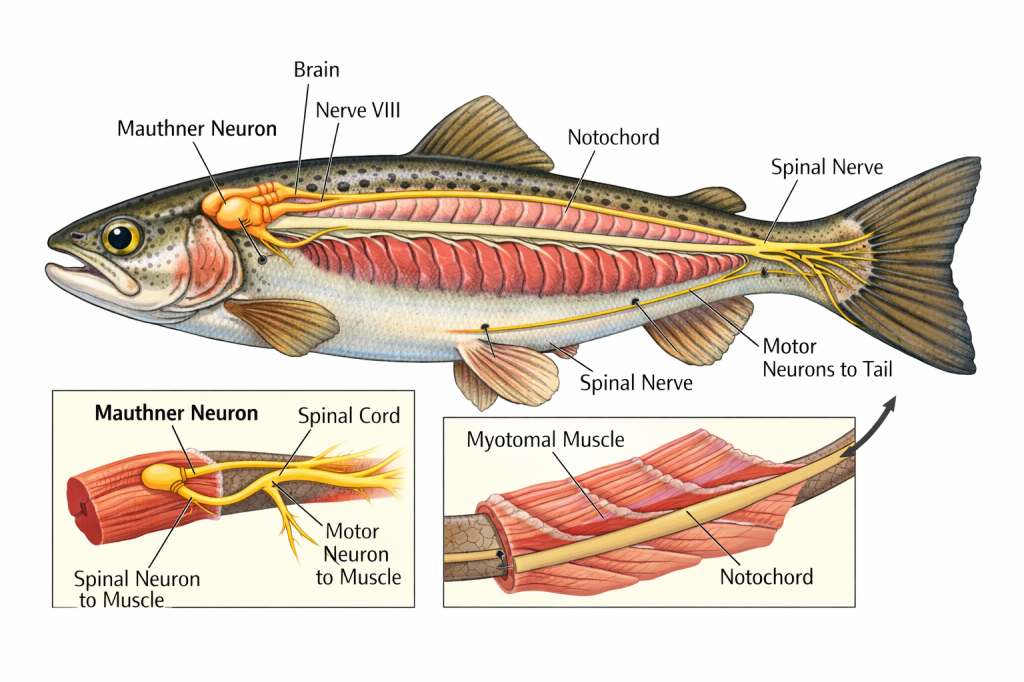

Mauthner neurons are found in relation to nerve VIII. They send a signal from the hindbrain directly to motoneurons in the tail and, upon startle, command a rapid tail-flip escape response. These neurons are not present in all fish, such as hagfish or adult sharks, but they are very common in many teleosts. This neural pathway explains the instantaneous darting response observed when food, bait, or even a rock is dropped into a fish tank or pond. The reaction is not deliberation—it is a hard-wired command that predates complex cognition.

Detection of these disturbances, however, begins even earlier. Aquatic vertebrates possess a lateral line system, a sensory organ that detects minute vibrations and pressure changes in the surrounding water. This system allows fish to perceive movement without visual confirmation. For anglers, this explains why stealth is more than remaining unseen. A heavy footfall on a bank, a sloppy lure entry, or a misplaced cast sends a pressure wave through the water column that contacts the lateral line long before the fish ever sees the angler. Water itself becomes a conductor of information. The fish does not merely live in the water—it feels the environment with its entire body.

A second structural clue linking fishes is the presence of myotomal muscles along the body. All living fishes, excluding higher teleosts, possess this flat sheet of muscle folded into a three-dimensional form. Each myotome is innervated by a single spinal nerve. This same pattern is shared with urodele amphibians such as newts and salamanders. The organization of these muscle segments enables efficient oscillatory movement and reinforces a shared anatomical plan consistent with a monophyletic origin.

This musculature evolved alongside structures designed to minimize energetic cost. Many fishes are optimized to reduce the “cost of transport,” the energy required to move through water. By exploiting vortex shedding—using swirling currents created by rocks, banks, or even other fish—fishes can hold position or travel efficiently while expending minimal energy. This is why fish occupy seams, eddies, and tailouts. They are not simply resting; they are positioning their bodies to harvest energy from the river itself. An angler who reads water is, knowingly or not, reading the evolutionary efficiency of the species.

With morphological clues such as these, combined with molecular data, there is strong evidence that all living members of the Pisces class share a common ancestor.

Chordates are organisms that possess a notochord—a flexible rod that serves as the chief axial supporting structure of the body—along with myotomal muscle along the body. Studies involving acraniate amphioxus, a marine chordate such as a lancelet lacking a skull or cranium, have shown through experimental fossilization that notochords and myotomes can survive extended periods of decay under anoxic conditions. Fossils preserving these features are rare, but they do exist. Among the more unusual discoveries is Pikaia, an amphioxus-like organism with V-shaped myotomes, a notochord, and a bifid head divided by a deep cleft. Pikaia is found in the middle Cambrian Burgess Shale of the Colorado Rockies and appears to have existed for only a brief geological interval.

In the Lagerstätten fields of Chengjiang in China, small fish-like chordates such as Cathaymyrus and Myllokunmingia swam approximately 530 million years ago. These organisms possessed complex gills similar to amphioxus and lacked a bony skeleton. As a group, their ancestors may have arisen in the Ediacaran era. These fossils show clear evidence of notochords and myotomal muscles adapted for oscillatory movement, yet they lack definitive traits allowing for uncontested classification.

Conodonts date from the Precambrian through the late Triassic period. Until 1983, only scattered calcium phosphate “teeth” were known, as these were agnathic organisms. Later discoveries revealed impressions of a notochord, V-shaped myotomal muscle structures, caudal fins, bone-like material interpreted as teeth, and large anterior eyes.

There is clear evidence that many different fish-like organisms existed that could plausibly be the ancestors of modern fishes. Evidence supports multiple interpretations, but from one chordate lineage—either the conodonts or amphioxus-like chordates—all living fish likely descended.

Although debate persists over whether all living fish are monophyletic, fossilized bony fishes appear in the mid-Cambrian period, roughly 600–500 million years ago. By the Ordovician, a wide variety of jawless fishes had already emerged. Classifying agnathans such as hagfish and lampreys remains contentious, resulting in two competing cladograms: one placing lampreys in close association, and the other treating them as sister groups.

This matters to anglers because it explains why fish behave the way they do and why certain patterns repeat across waters, species, and eras. The traits described here—lateral line sensing, Mauthner neurons, myotomal muscle structure, buoyancy control, and hydrodynamic efficiency—are not academic abstractions. They are the machinery behind escape responses, cruising efficiency, burst speed, and strike behavior.

Most modern teleosts possess a gas-filled swim bladder that allows them to achieve neutral buoyancy. This enables fish to suspend motionless in the water column without expending energy. A bass holding under a dock or a trout sitting effortlessly in a micro-eddy is not resting by chance; it is exploiting a finely tuned balance between gravity and water. For anglers, this explains why pauses, hangs, and slow retrieves are so effective. They mimic organisms that have mastered gravity within a liquid world.

Visual processing further reinforces this. Many fishes are optimized for contrast detection rather than fine detail. Certain flashes of color, vibration patterns, or movement trajectories trigger fixed-action responses—automatic strikes that bypass deliberation. Sometimes a fish is not fooled into thinking a lure is prey; its ancient wiring simply cannot refuse a specific sensory trigger.

For anglers, this knowledge strips away the illusion that success comes from novelty alone—new lures, new gear, new data. Instead, it returns attention to fundamentals: movement, pressure, flow, timing, and restraint. You stop asking what worked yesterday and begin asking what this body, shaped by hundreds of millions of years, can do in this water, right now.

Fishing, then, is not about mastering a species. It is about meeting something ancient on its own terms. The fish you hook is not just an individual—it is a surviving solution to time, water, and motion. Understanding that does not make fishing easier. It makes it more honest.

Leave a comment