A Method for Repairing Fly Fishing Leaders

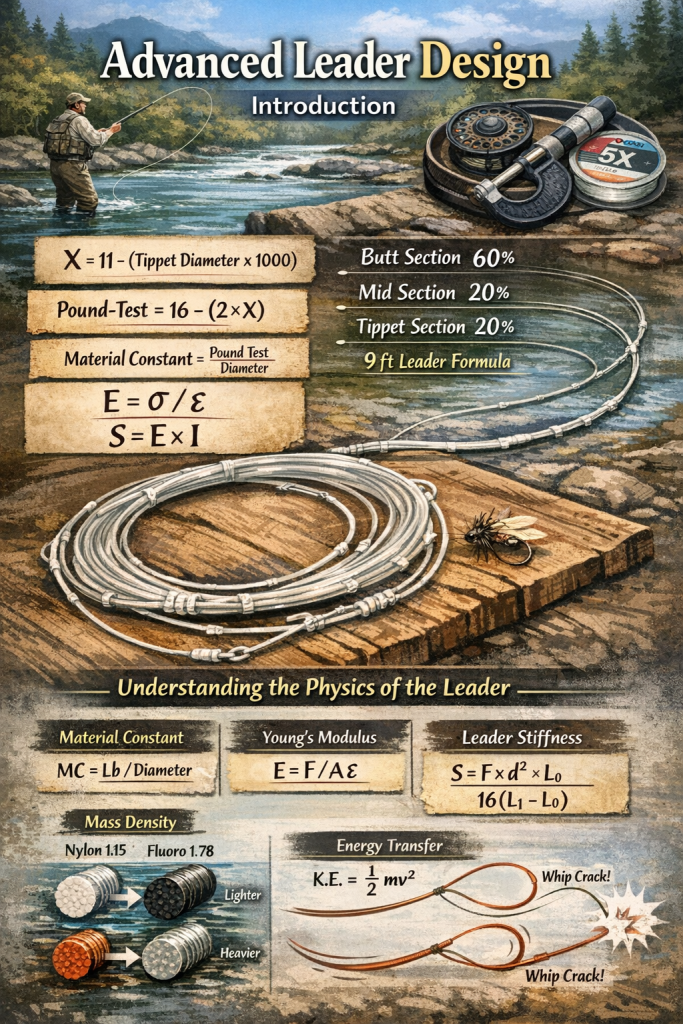

Introduction

We spend hundreds on high-modulus carbon rods and precision-machined reels, only to trust our trophy of a lifetime to a scrap of plastic we don’t fully understand. Having an affinity for mathematical principles, I pursued the art of the leader to be better prepared for the dreaded “snapping” of the leader. After every season of fishing, my leader wallet is stuffed with tapered leaders, knotted leaders, all short and stubby. Some caught in the trees, some caught on rocks in the river, and some broke because the fish managed to win. Last year, I set out to find a solution to the extra leader problem, only to discover a fluid system for building leaders from scratch.

A 60% butt section, 20% midsection, and 20% tippet over 7.5 to 9 feet is often referred to as the gold standard, however this may have sufficed in the days of horsehair and silkworm gut leaders. Today, we depend on polymers, which different properties than natural fibers and strings, leaving us to wonder, “how should we rig?” and “What is the best leader for this situation?” There are many formulas on the internet and in books, but to truly understand the physics of a leader, one must dissect the governing mathematic principles.

It is important to note:

1. The leader and tippet connect the fly line to the fly itself, offering invisibility in the water while still providing abrasion resistance and flexibility to reduce line breaks.

2. The length and strength of the leader and tippet vary to reduce line breaks or to present the fly as naturally as possible.

3. The length and strength of the leader and tippet vary depending on the fishing conditions and target species. Therefore, it is determined that having the right leader for the water being fished is essential in successfully catching your target fish.

Leaders are typically rated in three ways, by pounds (lbs) it takes to break in lab testing conditions, by diameter of the line, or by the ‘X’ system. Note: if the leader is rated by poundage, then it’s referring to the butt strength of the leader. As a fly angler in the field, you must always know the leader’s rated poundage, and either the tip diameter in ‘X’, or the tippet pound rating printed by the manufacturer. Most commercial tapered leaders list both: ”9ft 5X”. In the field knowing butt strength and tip diameter is enough to compute everything.

Originally, leaders and tippets were made from silkworm gut in the 1800’s. Gut strands were naturally tapered, translucent, and surprisingly strong. Anglers needed a way to sort the gut by diameter, because diameter determined visibility and strength. Early suppliers graded gut by thickness: extra drawn, standard, and stout, however this was vague. By the early 20th century, nylon replaced gut, and manufacturers introduced a numerical diameter scale so anglers could match leader formulas and tippet to fly size consistently. The rule is simple: each increase in ‘X’, the thinner the diameter.

Material Constant

The best way to determine the tippet size of these leaders is to refer to the manufacturer’s charts. However, many times these details are not available, so I use digital calipers. The digital calipers provide precise measurements, allowing me to know the exact thickness of the tippet. Match the thickness with the tippet material, such as fluorocarbon, making sure it is equal or lesser than the leader’s tippet diameter.

If the leader is rated by the ‘X’ system, then it is referring to the tippet of the leader. The formula for figuring the X rating:

X = 11 – (Tippet Diameter in thousandths of an inch x 1000)

To reverse the calculation:

Diameter (inches) = (11 – X) / 1000

This system provides anglers with a way to have precise calculations of tippet diameter and present flies subtly. To convert X-rating to pound-test:

Pound-Test = 16 – (2 * X-Rating)

Use the same brand and product type for your monofilament or fluorocarbon leader material, this ensures that the material constant, or linear strength coefficient, a breaking strength to diameter ratio, stays relatively the same. However, if you don’t use the same brand, don’t fret, the best way to tie a leader is to find the material constant of each section. Some material constants can be roughly the same for two different sized lines because the material breaking strength is dependent on the diameter. Say you’re fly-fishing for bass, and you have three spools for leader material: 15lb, 12lb, and 10lb. The 12lb and 15lb are the same brand, but the 10lb is a separate brand. The formula for a material constant:

Material Constant = Pound-Test (lbs) / Diameter (inches)

Repeat this for all the spools. For example, 15lb is 1087, 12lb is 1026, and the 10lb is 909. If I had a brand where the material constant of the 10lb was above 1026, then I would know not to tie on that brand, as the Material Constant of the 10lb would overpower the 12lb possibly leading to a break in the 12lb section. This is hard to do when materials are the same, however the more specialty lines will have noticeable differences to the generic lines.

If your numbers are consistently dropping as you calculate from the highest poundage to the lowest, then you are okay to tie it on from butt to tippet. Checking the material constant ensures that the leader’s strength is consistent throughout the entire length. Typically, when the leader breaks, only the tippet section should break off, leaving the repair simple and easy. Having one or two segments with different material constants can result in a break in an unwanted section of the leader.

Since different manufacturers produce lines and tippets with varying strengths, it is easy to not know what is the best to select. If you are going for finesse, or subtle presentations, then a lower material constant might be what you’re looking for. If you are fishing for powerful fish, or fish with teeth, then a higher constant may be what you need. The material’s strength might be guessable by the diameter, but finding the material constant helps you find consistency in the line strength. You can find the difference in Material Constant from the butt to the tippet and roughly find the strength of the mid-section.

Material Constant Example

For instance, say you have a 16lb tapered leader that broke off by 45%, leaving 55% left, but you want to continue using the 55%. What size line do you tie on to extend the leader’s tippet back out by the missing 45%?

1. Find the poundage of the tippet with the calipers.

Tippet Poundage = (Butt in lbs x Tip Diameter) / Butt Diameter

8.59lbs = (16 x 0.0145) / 0.027

2. find the material constant of the butt and the tippet (find one or the other because they should be roughly the same if you use decimals).

MC = 16/0.027 = 593

3. Take the calipers and measure the tag end of the leader. At 55% my leader reads 0.020.

4. Multiply the constant by the tag end to get the pounds:

Tippet Section (lbs) = 593 x 0.020 = 11.86 lbs.

So, then I know I need to tie the knot a little high, to reach the 12lb line, and use 12lb tippet. Remember these calculations are important if you are using a tapered leader, and especially important when using different brands.

Bridging the gap between the pound rating and the X system is done by using the material constant.

5. Rearrange the Material Constant formula to solve for diameter.

Diameter (inches) = Breaking Strength (lbs) / Material Constant

Use the X system formula to convert diameter to the X-rating. For example, Diameter = 16/592.59 = 0.027inches. X = 11 – (0.027 x 1000). This may be obvious, but when repairing or extending a broken leader in the field, this calculation becomes crucial to maintaining the correct taper and performance of your leader. By accurately determining the diameter and the corresponding X-rating from the pound rating, you can ensure that the replacement section matches the original leader’s characteristics. This preserves the leader’s ability to turn over properly during casts, delivering the same performance as the day you bought it. The only downside is that the MC doesn’t account for the material’s physical properties.

Elasticity and Flexibility

The second, and more accurate way of calculating the elasticity and flexibility of each section of the leader helps ensure there are no stiff spots in the leader. This will inherently boost leader’s unfolding performance. When the leader unfolds, it should unfold from most stiff to least stiff, and this must happen consequently to the tapering of the leader. However, to maximize the leader’s performance, it is good to make sure the leader has an even flow of elasticity from butt to tippet.

If you’re using mismatched fluorocarbon or monofilament brands, then this procedure may be more important than if you’re using spools of the same brand and, or more specifically, the same product line but in a different size. I will buy 20-50lb lines made by one brand, like Seaguar Blue Label or KastKing Durablend, generally less expensive, but it’s mainly butt material. I’ll purchase 8-15lb in a more specialized product or brand, like P-Line Tactical or Trilene. Finally, I’ll purchase 2-6lb as highly specialized products, like Rio, ensuring the tippets are always outperforming the butts, regardless of what size leader I am making. Frankly, this saves me a few bucks while only sacrificing performance in the butt material. With that said, the butt is not as important when hybridizing fluorocarbon and monofilament; the butt section generally performs better than the tippet; the butt section is typically reusable; using the mathematical principles here, branding does not apply.

Start by finding the elasticity of each section by looking for Young’s Modulus. Young’s Modulus isn’t a fixed number. It moves with temperature. Most fishing lines are tested at room conditions, around 70°F. But the moment that leader touches real water, the material is no longer behaving like it did in the factory.

In cold water, polymer chains lose kinetic energy and can’t flex as freely. The result is a higher Young’s Modulus — the line becomes stiffer and more brittle. In warm water, those chains move more easily, lowering stiffness and increasing elasticity, but often reducing ultimate breaking strength.

So, if you design or calculate a leader’s taper and flexibility in a warm garage, then fish it in a 40°F tailwater, the leader will behave stiffer than expected. The smooth energy transfer you planned can turn into rigid hinge points. Likewise, tropical flats push the material the other direction.

Temperature doesn’t just affect fish. It changes the physics of the leader itself.

Fishing lines are viscoelastic, meaning each time the line is stretched it becomes weaker and weaker; therefore a fresh leader is stronger than a leader that has fought a few snags. It’s also important to know that when fighting snags, it’s best to remove the hook from the caught snag; do not pull on the leader.

This information may be on the manufacturer’s website, but if you have trouble finding it, the procedure for calculating Young’s Modulus is simple with a little practice and a good calculator.

Young’s Modulus (E) is defined as:

E = σ/ϵ

Where σ is the stress, ϵ is the strain, or change in length.

σ = F/A

Where F is the force applied (in newtons or pounds) and A is the cross-sectional area of the line. Cross-sectional area refers to the size of two-dimensional surface you would see if you cut the fishing line perpendicular to its length and looked at the cut end, represented by:

A = pi * ((d/2)^(2))

Where d is the line’s diameterand ϵ is the change in length over the original length:

ϵ = (L1 – L0)/L0

The entire formula looks as follows:

E = (F/(pi x ((d/2)^(2))))) / ((L1 – L0)/L0)

The formulas look scary at first, but once the full process is understood, it’s very simple. First, cut three feet of the material to be tested. Tie a Perfection Loop on both ends and take note of the original length of the line, L0, from knot to knot. Attach one loop to something sturdy like a strong tree and the other to your fish scale. Slowly apply force, taking note of max poundage applied. Don’t break the line, stretch it. Monofilament will stretch easier than fluorocarbon so apply a force to stretch and then stop. The point is to get the minimum force to stretch the material by 0.005 of an inch or so. Measure from knot to knot again, L1, and take note new length.

Simply punch in the formula in your calculator with the appropriate numbers, using 3.1416 as pi. You should get something like 3.88 x 10^(10) Pascals (Pa), a very large number. Then convert it to Gigapascals (GPa) by dividing Pa by 10^(9). For example, 3.88 x 10^(10) / 10^(9) = 38.8 GPa. This number is important in finding the flexibility of the line, and I tend to write it on the spool or in a notebook with a Sharpie (along with other precise line properties I have calculated).

Young’s modulus calculates the stress per change in length—a fundamental variable when calculating the flexibility of a line. If the leader was stiff in the middle or certain spots along its length, it can significantly affect your casting performance, presentation, and overall fishing experience. A stiff section can disrupt the smooth transfer of energy from section to section, sometimes failing to straighten fully during a cast, or collapsing, leading to poor turnover.

A stiffer section will cause an unnatural drag on the fly, especially in currents. A stiffer section in part of your leader makes it harder to achieve a drag-free drift, which is crucial when nymphing or dry fly-fishing. When fishing streamers or wet flies, stiff sections reduce the natural movement of the fly, making it less appealing to fish. Typically, stiffness in the leader becomes a problem when making delicate fly presentations and natural drifts.

Stiff sections can make tying knots more challenging and make them more susceptible to breaking, especially when connecting softer tippet or adding additional sections. Mismatched stiffness between leader sections can result in weaker knots, as the stiffer material doesn’t cinch down as smoothly.

However, a stiff middle can help turn over larger, heavier flies by improving casting energy. In scenarios requiring abrasion resistance and strength, a stiff leader might be more preferable. Targeting species like muskie or tarpon calls for a strong, stiff leader, and using these methods may help you find the best material for your situation.

Stiffness in a leader can help withstand sudden bursts of force, providing better control during a fight. A stiff section helps prevent break-offs when the fish run through rough cover. Casting in windy conditions may call for a stiffer, less flexible material. This improves energy transfer through the air. Your leader is only as strong as the weakest link, and we determined the force needed to stretch the material, and we know the materials breaking strength and diameter, but what we have yet to calculate is the flexibility and the stiffness, to make sure there is a smooth transition of energy from the butt to the tippet, without each section being less stiff than the last. This number helps you determine which of the two tippet materials (of the same pound-test or diameter) is best for the situation.

The stiffness formula to begin with:

S = E x I

Where S is the stiffness, or flexural rigidity, E is Young’s Modulus, and I is the moment of inertia.(Use Young’s Modulus of the material in Pa). Moment of Inertia is a property that quantifies how resistant the line is to bending. This is a fundamental concept from physics, and while most commonly associated with rotating objects, it applies here to describe how the line’s cross-sectional shape and size affect its stiffness.

I = (pi * r)^(4) / 4

r = d/2

I = pi/4 * (d/2)^(4)

I = (pi/64) x d^(4)

The above formula is an approximation for comparative purposes, but fishing line flexibility/stiffness doesn’t typically need moment of inertia in practical angling use. In physics, the moment of inertia refers to an object’s resistance to rotational motion. In this case we are discussing flexural rigidity of the fishing line, which is the resistance to bending, like when the line loops and folds on the water. For thin, cylindrical objects like fishing line, the formula for moment of inertia helps quantify how the cross-sectional diameter affects stiffness.

Therefore, stiffness is determined by:

S = (F/(pi x ((d/2)^(2))))) / ((L1 – L0)/L0) x ((pi/64) x d^(4)).

Where L0 is original length and L1 is stretched length. Which simplifies to:

S = (F * d^(2) * L0) / 16(L1 – L0)

To ensure line stiffnesses:

S (Section z)/ S (Section y) x 100 = Relative Stiffness (%).

Aim for 30-50% stiffness between adjacent sections.

Flexibility is directly inverse to the stiffness calculated as:

Flexibility ∝ 1 / E x d^(4) or Flexibility ∝ 1 / Stiffness

Thus, we can see as stiffness increases, flexibility decreases. Conversely, as stiffness decreases, flexibility increases. In practical terms, if you are designing a fishing leader, the stiffness of a section depends on E x d^(4) or S ∝ d^(4). If you are comparing two lines of the same type, but different brands or product lines, then you can use:

S ∝ Material Constant × d^(4)

For the inverse, and to find the flexibility:

Flexibility ∝ 1 / Material Constant x d^(4)

If the diameter of the leader section doubles its stiffness increases by 2^(4) = 16 times.

If the diameter of the leader section triples its stiffness increases by 3^(4) = 81 times.

Designing the Leader by Stiffness Ratios

The diameter of two lines of the same product and brand could be used to find stiffness increase between two lines. If two lines are made from the same material formulation, then Young’s Modulus (E) is effectively the same for both. Therefore, differences in stiffness come almost entirely from diameter. Product A has a diameter of .027, and product B has a diameter of .011. To find the increase in stiffness:

Material Constant x (Diameter A)^(4) / Material Constant x (Diameter B)^(4) = Stiffness Ratio

(593 x (0.027)^(4)) / (727 x (0.011)^(4))

3.152 x 10^(-4) / 1.0647 x 10^(-5) = 29.61

Meaning Diameter A (the butt section) is 29 times stiffer than Diameter B (the tippet section).

Percent Increase = (Stiffness Ratio – 1) x 100

Percent increase (29.61 – 1) x 100 = 2961%

As we can see, going from a 16lb butt to an 8lb tippet would be a significant percentage increase. 2961% reflects a huge mismatch in stiffness. However, adding transition sections between the butt and the tippet help transfer the flow of energy. We want these percentages to be as low as possible from one section of the leader to the next, going from butt to tippet.

It is also wise to note that the strength of the next section of tippet in a leader should be dependent on the flexibility of the material, not the poundage, or diameter. Flexibility plays a crucial role in maintaining the leader’s performance and ensuring smooth energy transfer—which directly affects casting, presentation, and durability. If there is a sudden drop in flexibility, the leader won’t straighten out properly, resulting in hinging, wasting of casting energy, and poor turn over.

With flexibility as the key, we can calculate the midsection of the leader by using the governing physics formula:

Stiffness ∝ MaterialConstant × d⁴

For the midsection, we want the relative stiffness between the two adjacent sections to fall in a target band:

Sₙ / Sₙ₊₁ ≈ 1.3 to 1.5

This creates a 30-50% drop per step, thus the law is simply:

(MC ⋅ (d_n)^4) / (MC ⋅ (d_n+1)^4) = R

(d_n)^4 / d_n+1)^4 = R

D_n+1 = d_n ⋅ R^(-1/4)

Where: R = ~1.4

The angler can use this to step through the leader, section by section, until the proper tippet is reached, however, if the angler is using a 3 section leader such as a 60/20/20 or 70/20/10, then the correct solution is:

Sb/Sm=Sm/St

Because:

(d_b)^4/(d_m)^4 = (d_m)^4 / (d_t)^4

Solved:

(d_m)^8 = (d_b)^4⋅ (d_t)^4

Or

d_m = sqrt(d_b⋅ d_t)

This removes the arbitrary 25-30% rule and balances the butt and the tippet based on flexibility, not poundage or diameter. If you were to have two or more mid sections with equal ratios in stiffness pace then you can use:

d_m1 = sqrt(d_b⋅ d_m2)

d_m2 = sqrt(d_bm1⋅ d_t)

Most anglers focus on leader length or pound-test, but delving into material constants, diameter-to-strength ratios, and cross-sectional areas show a deeper understanding of how leaders behave under stress. This optimizes performance and allows for precision repairs without disrupting the taper or strength distribution. Techniques like these are game changers in technical fisheries like Western U.S. tailwaters. Whether targeting bass, trout, or steelhead, every aspect of your setup can make or break your success. Using these techniques ensures your leaders perform perfectly in stealth and strength. fly-fishing is about precision, and sometimes laying down the fly as gently as possible requires more than feel, but exact calculations for the best performance.

Linear Momentum and Density

Casting a leader is also about the transfer of energy, or the momentum of the line. The line would not unfold if it didn’t have the proper transfer of energy from the butt to the tippet. Kinetic Energy = 1/2mv^2, thus mass must decrease to maintain the velocity, or the conversion of momentum. If the mass drops too fast the loop “whip cracks” with excessive velocity, but if the mass doesn’t drop fast enough the loop sags and fails to turnover.

A 0.020” Nylon line has significantly less mass than a 0.020” Fluorocarbon line because the fluoro is much denser (Specific gravity ~1.78 vs. 1.15 for Nylon).

This is important because the formulas perfectly match stiffness when using all the same material i.e. all Nylon, or all Fluorocarbon, but when creating hybridized leaders, you might accidentally increase mass density, creating a “hinge” caused by gravity or momentum rather than stiffness.

Lastly, density determines the cutting power through the wind and the water. Fluorocarbon is much denser, therefore it sinks, monofilament is neutral, and suspends in the water. When designing a leader for dry flies, using fluorocarbon may be detrimental to the presentation of the fly, regardless of calculations.

*Underlined formulas are base formulas used for referencing in the field.

Leave a comment